GUEST ARTICLE: Trade secrets…How do you protect recipes and product formulations?

Companies instead need to rely on other forms of IP, such as patents and/or trade secret protections.

So what is a trade secret?

A trade secret is a formula, manufacturing process, pattern, device or compilation of information that derives independent economic value from not being generally known or ascertainable, and which is the subject of reasonable efforts to maintain its secrecy.**

A trade secret is a kind of property right. The property right is lost when the information that constitutes the trade secret is disclosed to others, or others are allowed to use it.***

How do courts decide if info is – or remains – a trade secret?

In the US, several factors are used to evaluate whether information is or remains a trade secret.

Taking a holistic, or ‘totality of the circumstances’ approach, courts will consider:

(1) the extent to which the information is known outside of the business;

(2) the extent to which the information is known by employees and others involved in the business;

(3) the measures taken to guard the secrecy of the information;

(4) the value of the information to the business and to its competitors;

(5) the amount of effort or money expended in developing the information;

(6) the ease or difficulty with which the information could be properly acquired or duplicated by others.****

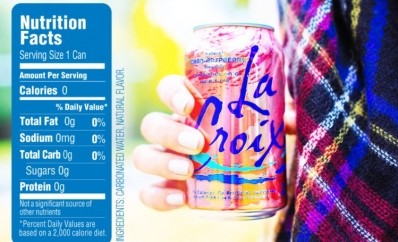

The food industry can experience particular challenges with these factors. This is because unlike high technology industries, everyone has some experience and knowledge of food and cooking; packaged food items must include a statement of ingredients in order of predominance by weight; there are typically many options for substantially similar food products on store shelves; and it is normal for multiple suppliers to participate in the process of bringing a final food product to the consumer.

Thus, it may be difficult to establish a trade secret for a formulation or a recipe process, and if reasonable steps are not taken such protections could easily be lost. The following court cases illustrate the issue:

Case 1: Trade secret pizza dough recipe (Magistro v. J. Lou, Inc., 703 N.W.2d 887 (Neb. 2005)):

This case raised the question of whether pizza dough and pizza sauce recipes garnered trade secret protection.

The party seeking protection testified that his family created their dough and sauce recipes in Sicily before they moved to the United States and that only family members were privy to the recipes. The business kept the recipes a secret by having immediate family members put the ingredients into packets and sealed them. An employee would later add water to make the sauce and the dough as needed.

The court found the recipes were trade secret primarily because the family took extensive efforts to keep the recipe secret. Only family members prepared the recipes and no one outside the family knew the recipes. Further, the dough and sauce recipes had organoleptic properties that when cooked up resulted in superior tasting products.

The combination of these factors established that the recipe would be valuable to a competitor and derived economic value from not being known.

Case 2: Trade secret chocolate chip cookie recipe (Peggy Lawton Kitchens, Inc. v. Hogan, 466 N.E.2d 138 (Mass. 1984)):

This case involving a chocolate chip cookie recipe shows how a novel process and innovative formulation can help a food product obtain trade secret protection.

The court acknowledged that, “no doubt,” the basic ingredients of flour, sugar, shortening, chocolate chips, eggs, and salt, would be common to chocolate chip cookie recipes. Even so, it credited that those basic ingredients could have trade secret protection because they could be uniquely combined, and the resulting cookies could be baked to different degrees, diameters and thickness.

Indeed, the court reviewed 40 other brands of chocolate chip cookies sold in the geographic area and noted that none of the recipes were the same. Further, the party seeking protection was using a “secret ingredient.”

The party seeking protection had also taken reasonable steps to keep the cookie recipe a secret. The recipe was carefully kept, with one copy locked in an office safe. A duplicate was locked in another location. When satisfied customers asked for the recipe, the company responded that the recipe was a trade secret.

For employees responsible for baking the cookies, the company broke down the formula into baking ingredients, small ingredients, and bulk ingredients. The three components were kept on separate cards which contained gross weights. Even though those cards concealed the true proportions of the ingredients, access to the cards was limited to only a few, long-time trusted employees.

Case 3: No trade secret for cattle feed (Weins v. Sporleder, 569 N.W.2d 16 (S.D. 1997)):

In this case about a cattle feed recipe, the court found that the recipe did not constitute a protectable trade secret.

The court took a ‘totality of the circumstances’ approach in reaching this result. First, the party seeking trade secret protection could not articulate what he was trying to protect, vacillating between whether the cattle feed or the cattle feeding system was the trade secret. If the party seeking trade secret protection could not identify its trade secret, the court was not going to step in and do it for him.

Second, the court found that the cattle feed was not novel: it consisted of a combination of well-known feed materials. As a result, the formulation was within the realm of general skills and knowledge in the industry. Further, an expert confirmed that the exact formula could be easily determined using an inexpensive chemical analysis.

Finally, the party seeking trade secret protection had not taken adequate measures to protect the secrecy of the recipe. For instance, while the product was in development, the party seeking trade secret protection had spoken with other companies about the product without having anyone sign a non-disclosure agreement. He had also left unsecured tubs of the finished product at a variety of ranches, making it possible for others to obtain and easily test (and reverse engineer) the product.

This last case is a clear example of what not to do if you want to ensure your trade secret rights are defendable in court.

Here are some best practices to consider for maintaining trade secret rights:

- Develop a trade secret protection policy and regularly update it as needed.

- Establish an IT and systems protection policy that uses security tools such as VPNs, encryptions and passwords to prevent cyberattacks. Restrict, secure and track/monitor access to databases, computer systems and shared drives containing recipes and processes with operational conditions and parameters. Use an automated document classification system that enables ‘Confidential’ marking of electronic and hard-copy information.

- Require all employees and contractors to sign confidentiality or employment agreements with comprehensive confidentiality provisions.

- Conduct onboarding training (in-person or virtually) with employees to explain the importance of maintaining confidential information.

- Implement demonstrable steps to ensure recipes/formulations will reasonably remain secret.

- Require third-parties to first sign a non-disclosure agreement before sharing any commercially sensitive information, such as recipe/formulation or processes.

- Educate employees on a systematic and documented basis about the importance of keeping company information confidential. This is particularly crucial now with work-from-home environments widespread.

- Restrict access to trade secret information and if required, only allow a select few ‘in the know’ employees or third parties who have signed confidentiality agreements to access such information.

- Require segmenting production-related responsibilities so that no one employee has the ingredient list and sequester manufacturing processes to multiple different facilities for making the final product.

- Ensure product formulations and processes are designed to not be ascertainable by reverse engineering by third parties. For example, this can be done by blending ingredients so that exact amounts are not detectable or identifiable through analytical means.

- Conduct exit interviews to ensure employees are aware of their post-employment obligations of confidentiality to deter misappropriation of confidential or trade secret information they learned at work.

Abby Meyer (left) is an associate in the business trial practice group and the lead associate for the food & beverage team at law firm Sheppard, Mullin, Richter & Hampton LLP. She is also a member of the firm’s class action defense, cannabis, and healthcare teams. Sara D. Vinarov J.D., Ph.D (right) is global legal head of intellectual property at Tate & Lyle.

Disclaimer: Ms. Meyer and Dr. Dastgheib-Vinarov contributed to this article in their personal capacities. The views expressed are their own and do not represent the views of current or former employers. This article is provided for information purposes only and does not constitute legal advice and is not intended to form an attorney client relationship.

* Publications Int’l, Ltd. v. Meredith Corp., 88 F.3d 473, 480 (7th Cir. 1996); 37 C.F.R. 202.1

** Uniform Trade Secrets Act; Restatement (First) of Torts § 757, comment b.

*** Ruckelshaus v. Monsanto Co., 467 U.S. 986, 1011 (1984).

**** Restatement (First) of Torts § 757, comment b.