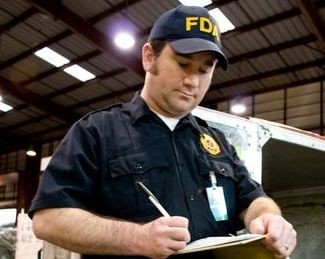

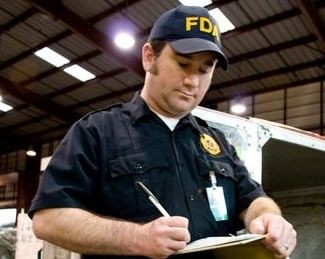

FSMA rule specifies ways to cut risk of intentional food adulteration

The rule, called in full FSMA Proposed Rule for Focused Mitigation Strategies to Protect Food Against Intentional Adulteration, was published on Dec. 24. The comment period on the rule extends to March 31 and a public meeting in College Park, MD is scheduled for Feb. 20.

The proposed rule specifies how domestic and foreign food companies must examine their operations to identify vulnerable processes where intentional adulteration could occur and come up with a plan to limit those risks. Food companies would be required to have a written plan in place showing how they plan to address the issue.

FDA says the goal is to protect the public from cases of intentional adulteration that are meant to cause large scale public harm. The agency notes that cases of intentional adulteration include acts of disgruntled employees aimed at harming a company’s reputation, intentional adulteration in which the goal is monetary gain and cases in which the goal of the perpetrators is first and foremost to cause widescale public harm.

It’s this last category that the rule is meant to address for the most part. FDA acknowledges that the risk of a large-scale attack via the food supply is low. But the potential for damage is high, saying “Intentional adulteration could have catastrophic results including human illness and death, loss of public confidence in the safety of food, and significant adverse economic impacts, including trade disruption, all of which can lead to widespread public fear.”

Solution in search of a problem?

Consultant Ben England, CEO of the firm FDA Imports.com LLC, said the proposed rule was mandated by FSMA and so FDA had no choice in the matter of issuing it. But England said he was hard pressed to come up with a example of a successful attack via food, and said having FDA address it in the first place is not a wise choice. And he said the call in FSMA for the proposed rule is indicative of some of the ways in which the law does not integrate well with how FDA regulates the industry.

“There are so many places in the law that it is clear that the people who drafted it didn’t know enough about the food industry. FDA is not a security agency. Customs would be better suited to do it,” England said.

“It turns out it is very hard to intentionally adulterate food and have a big impact. The bad guy has a couple problems. One, it’s difficult to put most poisons into food and not have the food spoil. Also, the poison then is so diluted it’s difficult to have an effect,” he said.

Focus on processes, not hazards

FDA said defending against such an attack requires a shift in thinking away from a focus on specific foods or hazards and moving more toward looking at what processes are most vulnerable. The agency’s own analysis identified the following four processes as presenting the highest risk, though the proposed rule does say that a company’s analysis of its own operation might lead to different conclusions.

The high risk operations identified by FDA include:

- bulk liquid receiving and loading;

- liquid storage and handling;

- secondary ingredient handling (the step where ingredients other than the primary ingredient of the food are handled before being combined with the primary ingredient); and mixing and similar activities.

Companies would need to address in their plan specific steps to be taken to mitigate the risk presented by the above processes (or others that a company might identify using their own methodology). The plan must include methods for verification that the mitigation steps are being taken, training steps and, of course, record keeping.

Phased rollout

The implementation of the rule is planned in three phases, with the biggest companies, those with more than 500 employees, being required to comply within one year of the finalization of the proposed rule. Companies with fewer than 500 employees would have two years and the smallest businesses, those with less than $10 million in annual sales, would have three years to comply. FDA estimates upfront costs for complying with the rule at about $70,000 per company.

Some food processes are specifically exempted from the risk analysis and mitigation steps, including the holding of food except for food in liquid storage tanks, “farm” activities and the holding, packing and shipping of food for animals.