Cultivated meat production is a complex process. In many parts of the world, regulatory approval has still not been achieved. One of the main barriers to commercialisation is cost, and one of the main costs is the use of growth factors.

Growth factors can not be done away with lightly: they are one of the most important parts of producing cultivated meat, as they stimulate the growth of cells. In order to promote growth, they must be added to the cell culture media, the mixture of nutrients which cultivated meat requires to work. However, they are also highly expensive and one of the main reasons why cultivated meat producers find it so difficult to produce at consumer-friendly prices.

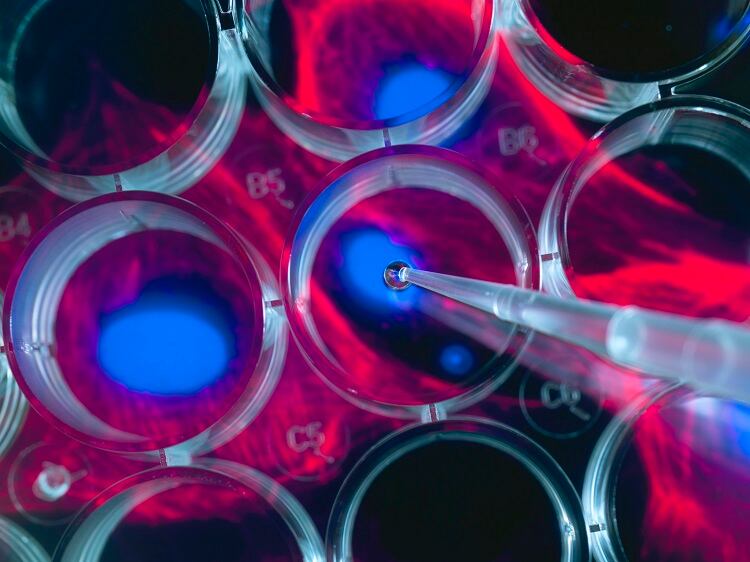

Now, a new study, published in the journal Cell Reports Sustainability, shows that bovine cells can be engineered to create their own growth factors, eliminating the need to add expensive growth factors to the cell culture media. This has the potential to be a boon for the industry.

“These kinds of systems offer the potential to dramatically lower the cost of cultured meat production by enlisting the cells themselves to work with us in the processes, requiring fewer external inputs (added ingredients), and therefore fewer secondary production processes for those inputs,” lead researcher Andrew Stout told FoodNavigator.

The role of growth factors in serum-free media

Growth factors are necessary because they provide a signal for cells to grow and differentiate. Fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), for example, trigger the growth of skeletal muscle cells. Without such a growth factor, cell growth decays. However, they are often a highly expensive part of the cell culture media, and must be frequently replaced.

For example, one culture media for immortalized bovine satellite cells (iBSCs), Beefy-9, relies on fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), a costly growth factor. After another costly component, the protein albumin, was replaced with rapeseed, the FGF2 remained the single most costly element, contributing around 60% of the cost.

“Currently, the price is high because the fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) are produced recombinantly, whereby bacteria are engineered to produce the proteins, and they are then harvested from those bacteria,” Stout told us.

“This involves an entirely additional bioprocess in which bacteria are grown in big tanks to make the growth factors, as well as expensive steps to harvest and purify them. It’s basically a second upstream ‘cultured growth factor’ process that is needed to be able to feed your ‘cultured meat’ process.

“A lot of the cost comes from that purification part, but there are costs inherent to the bacterial culture as well. It’s definitely possible to get the recombinant protein production cheaper for FGFs today, but the current scales and methods of production are still very expensive, and there will always be some cost to highly processed factors that are added as ingredients as opposed to having the bovine (or other meat) cells make their own.”

Engineering for lower costs

In order to remove the need for such costly growth factors, the researchers engineered the iBSCs to develop their own growth factor, meaning that they did not require the costly addition of growth factors to the serum. These cells were able to proliferate in a cell culture medium free of FGF2, dramatically reducing the cost of the production process.

“We inserted the gene for bovine FGF into the genomes of the cells in front of a promoter (a piece of DNA that helps accelerate production of proteins from genes) that we can turn on or off by adding a certain chemical to the cell culture. In other words, using the chemical like a switch, we can make the stem cells produce a lot of FGF, and then stop the production when we need to. This is important because after we induce the stem cells to grow with FGF, we need to turn FGF off so the cells can focus on transforming into mature muscle cells,” Stout told us.

However, the process is not ready for commercialisation yet, due to reduced growth rates and differentiation for engineered cells.

Nevertheless, the process has a lot of potential. It could in theory, Stout suggested, be used to grow cultivated chicken, fish and pork. It also has sustainability benefits.

“It’s likely that the process would improve the environmental metrics, since you no longer need that whole secondary recombinant growth factor production process (which uses energy, resources, etc) to support cultured meat production,” Stout told us.

Sourced From: Cell Reports Sustainability

'Engineered autocrine signaling eliminates muscle cell FGF2 requirements for cultured meat production'

Published on: 26 January 2024

Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crsus.2023.100009

Authors: A. J. Stout, X. Zhang, S. M. Letcher, M. L. Rittenberg, M. Shub, K. M. Chai, M. Kaul, D. L. Kaplan