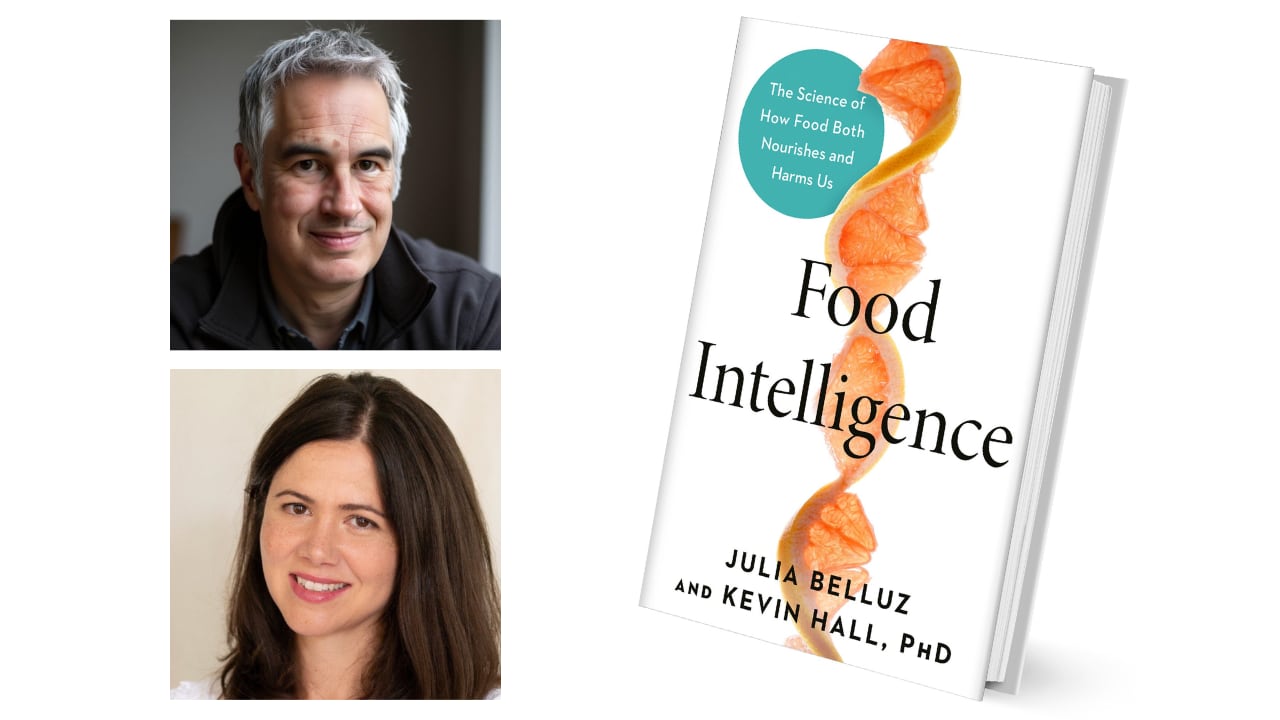

Food Intelligence: The Science of How Food Both Nourishes and Harms Us, a new book by acclaimed nutrition scientist Kevin Hall and award-winning health journalist Julia Belluz, examines enduring myths and misinformation about the food system and calls for more rigorous research into the ways our food may be undermining public health.

The book highlights Hall’s work at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which includes the landmark “Biggest Loser” study on metabolism and the groundbreaking inpatient trials on ultra-processed foods (UPFs). It offers additional insight from Belluz, who is a contributing opinion writer at the New York Times and health reporter at Vox and other major news outlets.

Hall and Belluz explore why the modern food environment makes overeating so easy, examines what controlled studies say about UPFs and serves as a guide for consumers, policymakers and the industry on how to improve the modern food system.

Misconceptions now and then

The book takes aim at modern nutrition myths, while contextualizing examples of diet trends throughout history. Hall and Belluz highlight the work of 19th century German scientist Justus von Liebig, who perfected the science of measuring the chemical makeup of organic substances like animal organs, bones and milk.

Liebig’s meat extract product, launched in 1865 as one of the first mass-marketed processed foods, made unsubstantiated claims about its medicinal value and “helped sow a meat panic and protein obsession that endures,” according to the book.

“It was embraced by the scientific community and the public, but it turns out many of the claims he makes aren’t founded,” Belluz explained.

Rushing to market on dubious assertions is a trend that has endured since Liebig’s day, according to Belluz.

“This is something Kevin and I just saw on repeat in this history of nutrition science, like so often, people running ahead with claims and ideas without bothering to test them,” she said.

Similarly, social media empowers unfounded health claims, but at a speed and scale never before seen, she said.

“What’s really difficult as consumers, is if you use any type of social media, you turn it on, and you’re bombarded with these health claims. It’s just like the currency of these different sites now,” she said. “Like so many self-proclaimed experts, they take something that maybe has a little bit of a grain of truth in it, and then nudge it in all these different directions that are completely divorced from science or evidence.”

This influence also is impacting public policy, according to Hall, who spent more than two decades as a research scientist at the National Institutes of Health.

“Right now, unfortunately in America, many folks in political leadership are the audience of this kind of misinformation and communication of health and wellness,” Hall said, adding that influencers have greater access to officials than career scientists and the agencies they govern.

Discrediting unsubstantiated claims can be an uphill battle for government officials because of public mistrust, according to Hall.

A common approach by influencers and companies pushing diet claims is that everything consumers have been told about nutrition is wrong, and their product holds the key to weight loss, he added.

“It’d be simpler if that were true, because then we’d have all these solutions in our back pocket, but the reality is that we often don’t have the research, and the science and nutrition research in particular has been pitifully supported, in the words of our last FDA commissioner, over the years,” Hall said.

The Biggest Loser

Hall became a substantial figure through his work on metabolism and weight loss, including his study of contestants on the weight loss reality TV show, The Biggest Loser.

“What wasn’t clear was exactly what was happening inside their bodies in terms of their metabolic rate, in terms of how much of the weight loss that we were seeing was coming from body fat versus muscle and other lean tissues in the body, and what was happening to their metabolisms,” he said.

Tests on contestants six years after the show concluded revealed that a common claim about exercise and weight loss was incorrect.

“The common theme being attributed in muscle and fitness magazines and from personal trainers that you could prevent the slowing of metabolism by doing all this exercise didn’t turn out to be true,” he said.

The study also debunked the belief that those with a slow metabolism were unable to lose weight.

“In fact, the people who were most successful at every point in time in this weight loss program were the ones who had the greatest slowing of metabolism,” Hall said.

Misunderstandings about metabolism is a running theme in Food Intelligence, which describes the public’s obsession with the topic as “a big distraction, not only for people seeking real help and answers, but from the insights that careful science over centuries has uncovered.”

Rather than being celebrated as core to the very existence of life, metabolism has become the body’s problem child, according to the book.

“The problem for most people is not a failure of biology. It’s not a slow metabolism. It’s not because of a particular genetic abnormality. It’s because the food environment changed,” Belluz said.

Do ultra-processed foods ‘rewire’ the brain?

Hall’s research on the food environment resulted in the groundbreaking 2019 randomized clinical trials that linked UPFs to weight gain. In the NIH study, two control groups were given separate diets – one containing UPFs and the other with minimally processed foods.

“What we found was that when these same folks were exposed to this ultra-processed food environment for two weeks, they ate about 500 calories per day, on average, more than when the same people were experiencing the minimally processed food environment, and they were gaining weight in the ultra-processed food environment,” he said.

Conversely, those in the minimally processed control group lost weight and body fat, the study found. The results raised bigger questions of whether the foods are addictive.

“Is it causing some rewiring of the brain, or something like that?” Hall asked.

More research is needed to better understand what causes some UPFs within the controversial NOVA classification system – which primarily classifies food based on processing level rather than nutritional value – to cause negative outcomes, according to Hall.

“I don’t think anybody at this point thinks that all ultra-processed foods within that very broad NOVA classification system are equally either bad for you or good for you, and I think the question then is, how do we make progress?” Hall asked.

HHS Secretary Robert F Kennedy, Jr’s Make American Children Healthy Again report, released in September, calls for establishing a government-wide definition for UPFs, but Hall questioned the efficacy of the government’s approach.

“It’s a little bit of a food industry talking point, in one sense, to say that there’s no universally recognized definition of ultra-processed foods. So until we have one, then we can’t do anything about this,” he said. “There’s no universally recognized definition of dietary fiber or whole grains or even a Mediterranean diet, and yet it doesn’t stop us from making recommendations and influencing policies and labels and things like that based on those kinds of considerations.”

The lack of science on UPFs conversely has the ability to hurt “innocent bystanders” in the food industry by inaccurately labeling products as unhealthy, Hall argued.

“What we’re seeing now is that pressure is being put on food companies to change the formulation of color additives, as if that’s going to affect the health of those particular products, and it might, but we haven’t done the science to know that yet,” he said.

The lack of adequate science behind these policies risks the political capital of forcing companies to change their formulations on products that could have little impact on health outcomes, he said.

“What you want to do is make big swings at things that you actually think are going to have a major impact on the health of Americans, because you’re going to expend all this capital on this. And I think the best way to do that is through better research,” he said.

Censorship at NIH

The book’s debut in late September comes about six months after Hall left a 20-plus-year career at NIH, claiming that federal officials censored his work and barred him from speaking with journalists about his study that ran counter to positions held by Kennedy.

Kennedy frequently has claimed sugar is as addictive as crack cocaine, but research by Hall examined changes in brain chemistry when consuming highly addictive drugs versus UPFs with high sugar content.

“No, we didn’t see that effect. It doesn’t mean that these foods might not be addictive for many people, and we talk about that a little bit in the book, and we talked about it in our scientific paper, but it just means that this particular biological mechanism didn’t seem to be at work,” he said.

Trump administration officials wanted to suppress the information because it contradicted their narrative, and Hall was told not to discuss it with the media.

It was not the first time Hall said his work had been suppressed by the Trump administration. Prior to the release of the report on addiction and sugar consumption, Hall was part of the American Heart Association’s author group for a statement on UPFs that included a section on health equity.

The NIH told Hall he would have to remove himself as an author unless the health equity section was removed because of the presidential executive order disallowing discussion of the topic.

“So instead of actually asking for censorship of my colleague on that section of the paper, I withdrew myself as an author,” he said.