Seafood farming is increasingly framed as essential to food security as the global population approaches 10 billion by 2050, but critics argue the industry is fundamentally unsustainable as the practice places more pressure on wild fish, harming ecosystems and contributing to climate change.

For seafood brands, responsible aquaculture factors into corporate climate targets and sustainability claims on packaging. Like any certification system, if these fail to deliver measurable outcomes, brands could face reputational and regulatory risk. But if governance, innovations in feed and accountability strengthen, aquaculture may provide a scalable, lower-carbon protein source aligned with hrands’ net-zero goals.

The case against ‘sustainable’ aquaculture

Aquaculture watchdog Aquaculture Accountability Project (AAP) argues in a recent report that seafood farming adds strain on wild fish, harms ecosystems, worsens climate change, spreads disease and promotes greenwashing – making it an unsustainable method.

One major concern is feed, according to the report. Carnivorous species such as salmon rely on fishmeal and fish oil, and AAP underscores the overfishing of small coastal fish to feed aquaculture salmon in the Global South. The report leans on global catch data and analyses surrounding the depletion of anchovy, sardine and similar stocks, arguing that aquaculture’s dependence on wild-caught feed continues to stress marine ecosystems.

AAP also challenges the aquaculture industry’s metrics. It claims the industry has “enshrined outdated and unscientific metrics into international law,” referring to feed efficiency ratios and fish-in fish-out (FIFO) indicators that critics say can underrate wild fish inputs as feed formulations evolve.

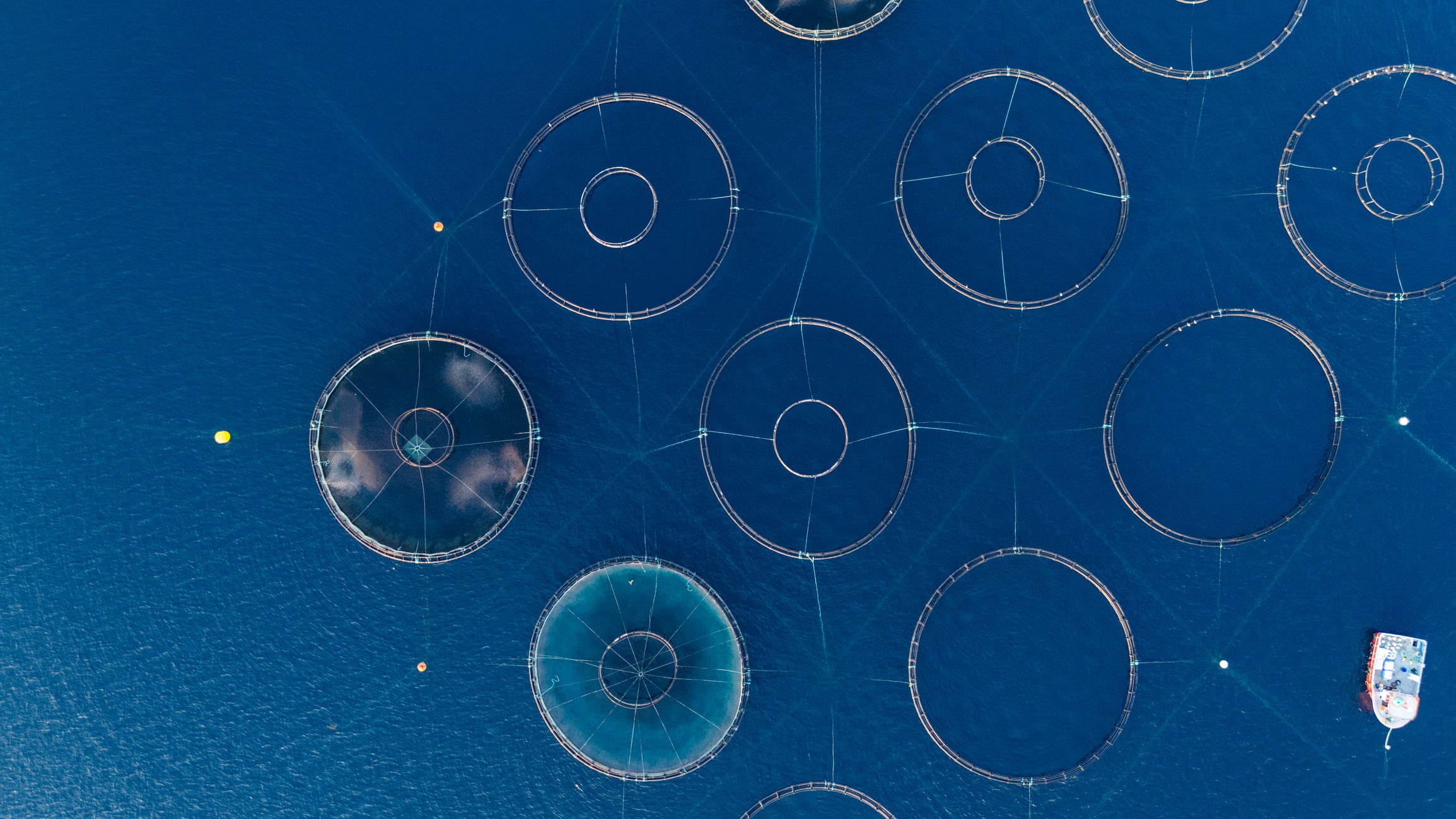

Disease from penned fish is another concern. Farmed fish, AAP argues, are crowded in pens, increasing the risk of aquatic outbreaks and antibiotic use that may spread to wild populations.

AAP also contests aquaculture as a climate change mitigator. The report combines global seafood consumption datasets and market analyses suggesting that aquaculture adds to total seafood supply rather than substituting for wild catch. This boom in seafood supply increases overall consumption and, in turn, leads to environmental harm, according to AAP.

In this framing, certification programs are part of the problem, offering marketing claims rather than meaningful reform, AAP argues.

The regulatory and certification counterargument

Aquaculture, or seafood farming, now supplies more than half of global seafood and supports millions of livelihoods, according to the certification organization Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC).

ASC calls the AAP report “a selective and misleading picture of seafood farming that risks undermining progress in responsible aquaculture at a critical time.”

“With wild fisheries at ecological limits,” ASC argues, “the issue is not whether aquaculture should exist, but how it is responsibly developed and managed.”

ASC defines sustainability through “measurable outcomes, independent audits, transparency and continuous improvement” under its Farm and Feed Standards. While ASC does not claim aquaculture as an impact-free practice, it affirms that its role is to reduce environmental harm and drive accountability.

On feed, ASC’s program requires full ingredient transparency, low-risk marine sourcing and alignment with ISEAL-compliant programs such as MarinTrust and the Marine Stewardship Council. Certified feed mills must measure and reduce environmental and greenhouse gas impacts using ASC’s GHG Calculator. According to ASC, this multi-prong approach incentivizes improved fisheries management rather than exploitation.

On antibiotics and disease, ASC-certified farms operate under strict controls, including prohibition of World Health Organization “critically important” antibiotics and zero antibiotic use in certified shrimp. ASC-certified farms much adhere to preventive fish health plans, water quality controls and ecosystem monitoring, along with defined sea lice reduction targets and public disclosure.

ASC also emphasizes climate accountability. It is “the only certification requiring farms to measure and manage GHG emissions through a standardized, life-cycle-based calculator.” Certified farms are required to monitor energy and water use, improve feed efficiency and adopt lower-carbon technologies.

Certification decisions are independent with public audit data and a dedicated Monitoring & Evaluation program tracking impacts, ASC notes. The organization states it is financially independent and does not receive producer fees.

A systems perspective: risk and governance

Federal scientists and marine researchers argue that aquaculture’s risks are governance challenges as opposed to proof of unsustainability.

Research published in the ICES Journal of Marine Science indicates the aquaculture industry is “ready and willing to expand restorative aquaculture,” yet warns that without policy, research investment and regulatory reform, the shift from restorative to sustainable models “will not occur at scale.”

The authors define restorative aquaculture as systems that improve ecosystem function while producing food – but identifies regulatory misalignment, ecological gaps and market barriers as major obstacles.

Similarly, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) notes that when finfish farms operate in open water, “water moves freely between farms and the ocean,” creating risks such as “the amplification and transmission of disease between farmed and wild fish.”

At the same time, NOAA describes aquaculture as a “net protein producer,” using about half a metric ton of wild whole fish to produce one metric ton of farmed seafood. Rising fishmeal and fish oil costs also drive the use of alternative feeds, including plant-based ingredients and fish processing trimmings. While disease outbreaks can occur due to higher stocking densities, “many farmed fish are vaccinated,” and antibiotics are “rarely used” and strictly regulated.

Sustainability is a governance questions

Aquaculture’s critics and defenders agree on one point: impacts must be managed.

ASC argues that “real accountability comes from measurable requirements, independent oversight, and transparency.” AAP asserts that current systems fall short.

The gap between those positions appears less about whether aquaculture can be sustainable and more about whether the policy, regulatory and market frameworks in place are strong enough to make it so.

Without methodical policy, research investment, regulatory reform and credible accountability, aquaculture may magnify environmental strain. But with those systems aligned, aquaculture proponents argue, it could lessen pressure on wild fisheries, protect ecosystems and support coastal communities.