“This lab is a start to that future,” he told an audience of visiting food scientists in the library of the Carl Schurz High School, which is host to an eponymous food science lab Guerrero established in 2015. The school visit was organized by the Chicago Section of the Institute of Food Technologists (IFT).

Nestled in the lush residential neighborhood Irving Park, northwest to Chicago’s urban core, the school’s food science lab is part of a growing network of hydroponic farms in the city, but so far the only one that also features the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)-designed food computer deeply embedded into a high school curriculum.

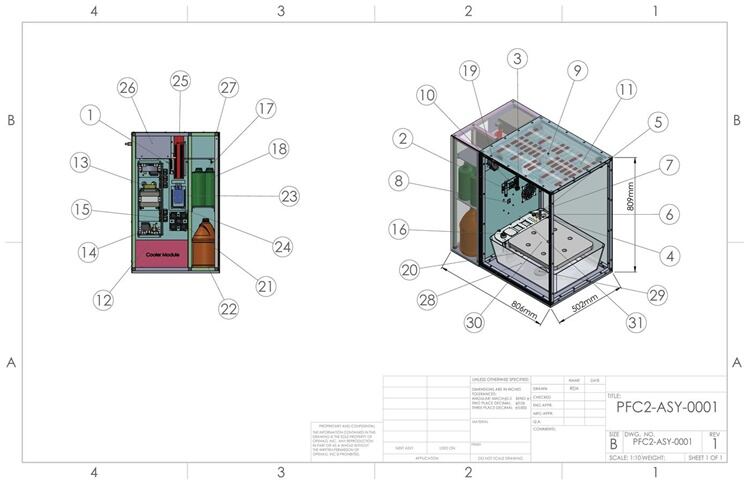

The incubator like computer was built using an open-access blueprint developed by MIT’s Media Lab researchers. It creates a highly controlled environment which replicates agricultural climates, and it’s up to the programmers (or students) to design and save codes that tell the computer how to optimize environments for specific crops to grow in it.

Key to a sustainable future for food

The food computer, when programmed right, helps crop-growers avoid the capriciousness of seasons, drought, and disease, and uses less space than an outdoor garden, and up to 90% less water.

By opening it up to educators around the country like Guerrero, it creates multiple R&D centers in which the computer can evolve, with a diversity of minds and hands working on it.

Food computer discoveries from the multiple high schools and universities can then be shared in the community-built OpenAg Wiki page, managed by MIT.

For Guerrero, having high school students work on the computer is a crucial part of building a sustainable future for food.

“With young kids, and young minds, they have no baggage—they’re eager to open their minds and learn faster,” he told FoodNavigator-USA. “Putting this opportunity in front of them is incredible because they can push it further than anyone else can do later in life. They can do things fresh and try things that we’ve potentially never thought of before.”

Getting more hands on with food

The long-term vision aside, food science programs that introduce food production and processing concepts to American high school-aged students are something more educators should jump on, Guerrero argued.

Farmers in the US continue to decline in numbers, according to USDA data from 2012, the last time an agriculture census was conducted. In addition, the average age of US farmers continue to climb.

The outlook is less somber when it comes to food manufacturing, which contributed more than all of the net new manufacturing jobs over the past year, and was able to provide over 100,000 more jobs than before the recession compared to manufacturing in other fields (which are still below pre-recession numbers), according to Bureau of Labor Statistics numbers crunched by economists Gad Levanon and Diane Lim for The Hill.

Guerrero hopes that high school educators can become catalysts in building a workforce that can meet the demand for skilled workers in the food industry, as well as help meet the demand for food of the American public.

To high school senior Niomi Manigault, 17, the food lab’s influence on the student body at large, and their relationship with food, is quite clear.

“People don’t get enough vegetables in their diets—some kids walk in with a Cheetos and a Sprite for breakfast,” she told FoodNavigator-USA. But with the Food Lab around—which provides some microgreens and herbs to supplement the Aramark-provided cafeteria lunches, “a lot of the students here eat salad for lunch.”

“People don’t want to go and plant food anymore, I saw traditional farming as something that’s dirty, and so much work, but after seeing there’s a more efficient way to grow plants and eat healthier, it seems more like a [doable] job,” she added.

Can water give soil a run for its money?

Counter-intuitively, growing lettuce and other leafy greens in water uses considerably less water than growing them in soil, but will hydroponic forms of agriculture remain a niche part of the food system, or can water give soil a serious run for its money?

Get the lowdown at FOOD VISION USA in Chicago this November, (13-15) when Suncrest USA CEO James Day will explain the merits of a technique called Deep Water Culture (DWC) hydroponics pioneered at Cornell University, whereby seedlings are planted on small rafts that float in large tanks of nutrient-rich, oxygenated water.