From mush to meat? Talking edible scaffolding for cultivated meat with Gelatex and Matrix F.T.

Right now, one option for startups looking to launch with a minimum viable product that could work in processed meat products is simply to proliferate muscle stem cells (feed them so they divide and multiply) and then harvest the undifferentiated cells – which have the consistency of Jello because they have not yet differentiated and matured into muscle tissue – and add other ingredients such as fats and extruded plant-based proteins to provide texture and mouthfeel.

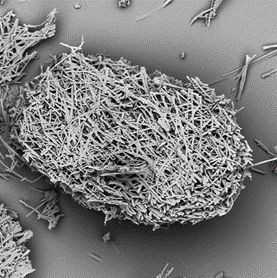

But for second and third wave products, companies are looking to edible scaffolding to recreate the extracellular matrix of meat, a complex web of proteins infusing meat that not only provides some texture in and of itself, but also influences the way cells differentiate, fuse, and mature into tissue, says Gelatex CEO Märt-Erik Martens, who was speaking to us after opening a new research, engineering and manufacturing facility in Tallinn, Estonia.

“A lot of companies are focusing on this first step [proliferating cells], but they are already thinking about the next step, because if the cells are [undifferentiated], the biomass is just like mush, like paté, it’s not really what we think of as meat.”

Gelatex: High throughput nanofiber spinning technology

Gelatex is using high-throughput nanofiber spinning technology for its shelf-stable, edible scaffolding in a continuous process, which Martens claims can achieve higher throughputs than electrospinning (applying electrostatic force to make polymer fibers).

According to Martens, who claims Gelatex is working with 30 cultivated meat companies: “Electrospinning is amazing. I have worked with the technology for a long time, but it doesn't scale up. Same with 3D bioprinting [another technique being deployed to texturize cultivated meat; although proponents beg to differ with Martens as to its scalability].”

Gelatex, he claimed, has developed “an industrial machine that occupies less than 10 m2 that is capable of producing up to 5 kg/hour of [edible scaffolding] material" in rolls (the width of which can be customized) which can be supplied to cell-cultured meat companies just like rolls of packaging.

Put simply, he claimed, “We can produce more nanofibers with one production line, and the initial investments to set up one production line, is multiple times less expensive, compared to electrospinning. So combining these two aspects - lower initial investment and much higher throughput - enables us to reduce the cost of nanofibers up to 90%. Due to much higher production speed and smaller electricity consumption, production costs are lower.”

As for capacity, he said, “Gelatex plans to double the volume by the end of the year, providing sufficient scaffolds for the manufacturing of 300 tons of cultured meat annually.”

‘Two different forces at the same time that enable us to pull the fibers much more quickly’

So how does Gelatex’s patent-pending technology work?

The first step is the same as it is in electrospinning, he said. “You dissolve a polymer in some kind of solvent. But instead of applying a high voltage electrical field to pull the fibers, we are using other forces. I can’t specify exactly what we're doing, but we are using two different forces at the same time, that enable us to pull the fibers much more quickly, and evaporate the solvent faster to obtain much higher throughput and yields.”

‘We’re working with all the plant-based polymers you can think of, including corn protein’

As for scaffolding materials, Gelatex – which as its name suggests, has worked extensively with gelatin (an animal product, although it can be produced by microbial fermentation) - is “working with all the plant-based polymers you can think of, including corn protein,” said Martens.

“It’s edible, the cells love it, it doesn't dissolve in water, and it’s a byproduct from the ethanol industry [or corn starch production], so we’re not taking [diverting] it from the food supply.”

Crucially, he said, “We can quite easily change things like fiber diameter, porosity, or whether fibers are aligned in let's say two or three directions. We can also do alignment in one direction as well to better facilitate cell differentiation into muscle tissue.”

He added: “We’re also building our own cell lab [to test how cells interact with the scaffolding] to better facilitate the improvement of our scaffolding for the cell cultured meat industry.”

Matrix F.T. ‘Electrospinning has been around a long time, and scaled in a lot of other industries’

Ohio-based Matrix F.T., meanwhile, insists that its approach to nanofiber edible scaffolding - electrospinning – is scalable, with VP corporate development Teryn Wolfe pointing out that electrospinning "is a technology that's been around a long time and scaled in a lot of other industries," most recently in billions of N95 masks.

Matrix F.T. – which is dissolving polymers in a solvent and then applying electrostatic force to create fibers which are then collected on a drum – has just opened a wet lab to accelerate multiple custom scaffold projects for its cell-cultured meat customers, said Wolfe.

Previously Matrix was waiting for feedback from cell-cultured meat companies about how their cell lines interacted with its scaffolding in order to refine and iterate its products, which was not ideal, because startups often lack the bandwidth to provide detailed feedback, and have concerns over protecting their IP, she said.

“Now, we have a couple of different types of cell lines in our lab that we're using for experimental purposes to see how they're working with our scaffolding, and innovation has gone through the roof.”

‘Everything that comes out of our lab is edible and animal-free’

According to Wolfe, “You can electrospin with any kind of biocompatible polymer, and we're using things like soy, corn, pea protein, alginate, and other plant-based powders, but everything that comes out of our lab is edible and animal-free, and can be included into a final food product, including food-safe coatings.”

The scaffolding itself (imagine something that looks like an absorbent paper towel) is also tunable, such that Matrix F.T. can adjust the alignment of fibers, or apply coatings that provide instructions to the cells as they differentiate and mature into tissue, she added.

‘I think a lot of people saw that making whole cuts is going to be really hard, because consumers have an expectation of what a whole cut of meat should look like’

But how much demand is there for scaffolding in the cultivated meat industry right now, given that only a handful of companies are even at the pilot stage, the regulatory process takes time, and the first wave of products is likely to include mostly unstructured products that don’t necessarily need sheets of scaffolding?

For adherent cell types, Wolfe pointed out (which need a surface to attach to), even the initial growth and proliferation phase requires some kind of scaffolding, typically in the form of tiny floating microcarriers (if you’re trying to grow such cells in a big tanks full of growth media, rather than on a bunch of petri dishes, they need to attach to something floating in the growth media).

Microcarriers are tiny beads to which cells adhere as they grow and divide in suspension culture (they basically mimic extra-cellular-matrix characteristics such as stiffness, topography, and porosity), said Wolfe, noting that Matrix F.T. can supply microcarriers from the same bio-materials deployed to make its sheets of scaffolding for more complex structured products.

Microcarriers from corn protein (zein)

One such is zein (corn protein), which the company (formed in 2019 via a joint venture between Nanofiber Solutions and Ikove Capital)claims can increase cell density in suspension culture.

“I think a lot of people saw that making whole cuts is going to be really hard, because consumers have an expectation of what a whole cut of meat should look like,” said Wolfe, “so they are starting with more unstructured meat, so as a result, we have started making a much greater effort in R&D for microcarriers as well.”

The microcarriers are customizable and can be introduced into down-stream processes such as differentiation scaffolding and 3D printing without removal of the cells, she added: “We’re using the same materials for the microcarriers as for the scaffolds, so when you introduce the scaffolding [to a bunch of cells that have been growing on microcarriers] they don't affect what the cells do once they get on to the scaffold.

“There's just more surface area for them to do their thing and then start that differentiation phase [where they start to fuse and turn into muscle fibers, for example]. We can make micro carriers that will degrade, or they can just become a part of the mass that goes onto the scaffold.”