In theory yes, but without a significant shift in current focus, it is highly improbable.

Comparatively, biofuels have offset roughly 10% of US gasoline in 15 years is a good example to predict the obstacles novel proteins - from egg and milk proteins from engineered microbes to cell-cultured meat and novel proteins from algae and other ancient micro-organisms - will face.

The record for biofuels has been mixed with both successes and failures, and there is a critical need to learn from this journey. Decades in biotechnology commercialization has confirmed the need to challenge historical perspectives, but also provides confirmation they should not be ignored.

The similarities between novel protein and biofuels commercialization are striking, and I am encouraged by key differences that make the novel protein path less risky. The key lessons learned from biofuel commercialization highlight my thoughts:

Long term cost parity is key to wide range acceptance

Most novel protein start-ups target higher value markets for initial product launch, to limit cash burn and provide more control on initial product usage. While this is a wise and valid approach, the ability to make a material impact on animal protein use requires long-term cost parity with traditional animal proteins.

The challenge of reaching cost parity is much different than bringing a novel product initially to market, which requires a shift in company focus from discovery and research phase, into low-cost manufacturing. This change in company focus to production with addition of experienced manufacturing personnel is an area where many startups struggle.

Carnivore capitalism

A high proportion of funding into novel proteins to date has come from mission driven ventures, with a focus on animal rights and/or environmental sustainability. These investments have been critical to the early success of novel proteins, as initial funding is often the most difficult to secure.

While mission driven ventures are looking for a financial return, there is generally less of a “cold hard capitalist” edge and a higher focus on the path the company needs to follow during commercialization. A common example is hesitance to work with meat producers or use animal products for focus group testing.

While the perspective is admirable, it can restrict progress and reaching the end goal. This often produces the quandary of which is more important, the path followed or reaching the goal. In the long term, for novel proteins to make a significant impact in offsetting animal farming, the technologies need to provide returns that attract traditional funding sources, including carnivores.

Playing both sides

Surprise is often expressed that major agriculture companies are investing in novel protein companies, while at the same time supporting efforts like labeling laws that are seen as resistant to the novel protein movements. These swivel-head efforts would appear to conflict, but these are lessons the large petroleum companies ('big oil') learned by trying to fight first generation biofuels (corn ethanol), where they attempted to limit adoption and failed.

By being in opposition, when they lost the effort, they had limited input on how implementation would occur, something they significantly regretted. By contrast, big oil participated in development of many second generation biofuels technologies, at the same time many of them were fighting industry regulations such as the renewable fuel standard.

Much like donating money to both candidates in a political race, the goal is to have influence no matter which outcome is reached.

I am from the government and here to help

The question of whether governmental support will be a net benefit to novel protein commercialization is difficult to answer. Meeting the proposed targets for replacing animal proteins will require hundreds of billions of dollars of investment, a level that will stress non-governmental debt resources.

While federal funding was certainly an impetus for biofuels commercialization, it also led to many of the failures by incentivizing over expansion before the market and technologies were ready. A secondary concern is that government funding brings political influence into the process.

There are many cases in biofuel funding where the congressional district where the project was located was as important as the maturity of the proposed technology. Federal funding may well be required, but brings downsides attached to the funds.

'All of the above' is the answer

The wide range of existing technologies that produce meat and animal replacement products provide avenues to success.

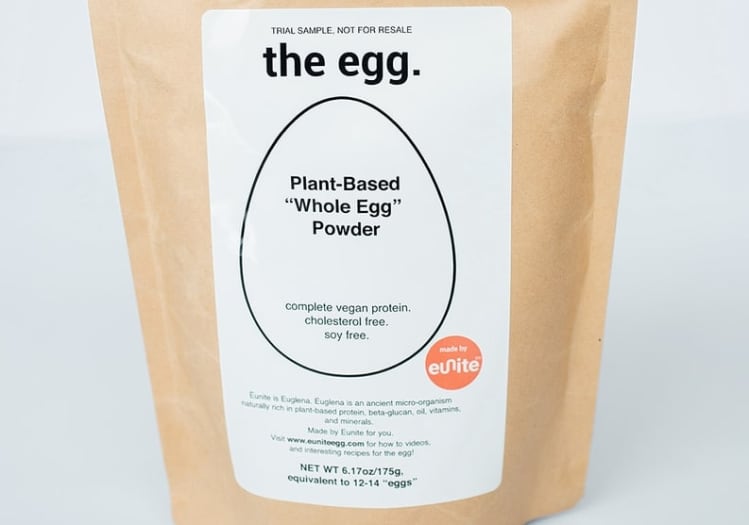

The industry includes processes for making animal proteins from engineered microbes (Perfect Day, Geltor, Clara Foods), heme proteins for plant-based meat (Triton, Impossible Foods), novel proteins from various micro-organisms (Sustainable Bioproducts, Noblegen), derivatives of agricultural proteins (Beyond Meat, Just Scramble) and cellular-based proteins (Memphis Meats, Finless Foods).

The key to large scale animal protein replacement is acknowledgment that all of these novel technologies are required to provide full market penetration against traditional animal products, rather than novel protein companies focusing their competitive efforts against each other.

The good news...

The technology commercialization risk is not as high in novel proteins as biofuels, where technologies were being developed to do something that had never been done before.

By contrast, most of the technologies used for novel protein and cell culturing have been commercial for many years, but in pharmaceutical production where cost is much less of an issue because sales prices of the final products are orders of magnitude higher than food products.

This means that proof of concept can often be quickly reached, with the primary challenge to adapt the technology to produce product at a lower price point. This is certainly a challenge, but with less technology risk than biofuels.

The other key benefit is the ability of novel proteins to get long-term product offtake contracts to support project financing. By contrast, long-term contracts are not common in the fuel industry where supply risk is mitigated by commodity hedging. This may sound like a minor issue, but will be key in opening up debt markets for required project funding.

Summary

Commercialization of plant-based novel proteins has many critical benefits and is key to sustainability of our planet. The technologies being developed are impressive and target the right areas, but the path to commercialization has many obstacles along the way.

Utilizing the lessons learned from recent biofuel efforts provides valuable insight to keep from forging a completely new path to commercial success. Much like when hiking and identify footprints in the snow, if the destination being sought is the same as those that came before you, it is often a quicker and more efficient path to following the footprints.

Mark Warner has held executive level positions with industry leaders such as Impossible Foods, Solazyme and Harris Group, focusing on taking first-of-a-kind-technologies from bench-top to commercial operation. He is the founder of Warner Advisors and author of Biotechnology Commercialization Handbook – How to make protein without animals and fuels and chemicals without crude oil