In the study, published in Public Health Nutrition, a nationally-representative pool of 1,030 US adults (researchers noted higher education respondents were moderately over-represented) responded to a survey with photos of both hypothetical and real products with various whole grain labels on the front of the package, along with nutrition facts labels and ingredients list for each product.

Participants were asked to identify the healthier option (for the hypothetical products) or assess the whole grain content (for the real products).

Consumer confusion over whole grain content

Respondents were presented with a pair of hypothetical products. In each pair, one product was nutritionally superior or inferior based on the disclosed nutrition information, which included added sugar content and major ingredients (e.g. corn, salt, sugar), said researchers.

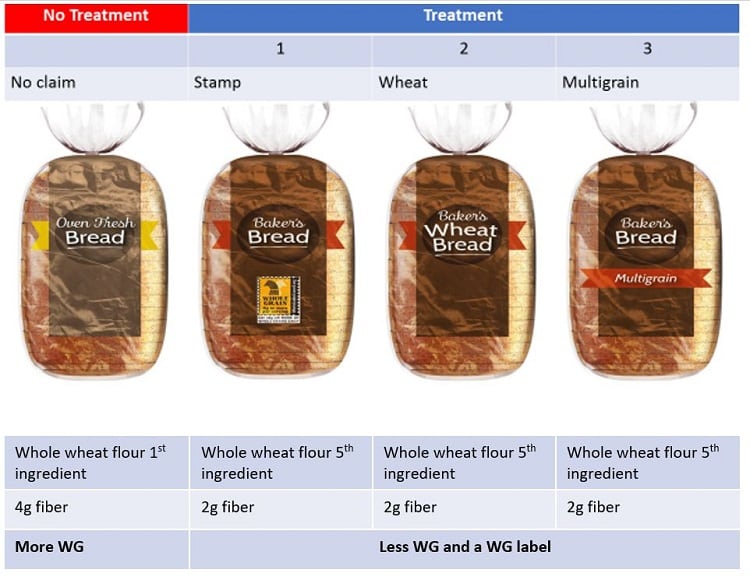

The packages on the hypothetical products either had no front-of-package whole grain label or were marked with "multigrain," "made with whole grains," or a whole grain stamp.

When asked which product was “healthier,” 29-47% of respondents answered incorrectly (specifically, 31% incorrectly for cereal, 29-37% for crackers, 47% for bread).

There were 3 randomly-assigned variations of the label within each of the 3 product categories: cereal (1 Made with WG, 2 Multigrain, 3 WG stamp), crackers (1 Made with WG, 2 Multigrain, 3 WG stamp), and bread (1 Multigrain, 2 Wheat, 3 WG stamp). Each respondent received only 1 variation within each product category.

For real products, 43-51% of respondents overstated the whole grain content (specifically, 41% overstated for multigrain crackers, 43% for honey wheat bread, and 51% for 12-grain bread).

Researchers noted that consumers more accurately stated the whole grain content for an oat cereal product that was mostly composed of whole grain.

"Our study results show that many consumers cannot correctly identify the amount of whole grains or select a healthier whole grain product,” said lead author of the study, Parke Wilde, a food economist and professor at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University.

“Manufacturers have many ways to persuade you that a product has whole grain even if it doesn't. They can tell you it's multigrain or they can color it brown, but those signals do not really indicate the whole grain content."

‘We have a strong legal argument that whole grain labels are misleading’

The goal of the study was to assess whether consumer misunderstanding of the labels meets a legal standard (i.e. evidence that labels are actually misleading or likely to mislead) for enhanced US labeling requirements for whole grain products.

"With the results of this study, we have a strong legal argument that whole grain labels are misleading in fact. I would say when it comes to deceptive labels, 'whole grain' claims are among the worst. Even people with advanced degrees cannot figure out how much whole grain is in these products," said co-author Jennifer L. Pomeranz, assistant professor of public health policy and management at NYU School of Global Public Health.